the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2022 Beverley Kane, MD

Page 13 of 20

selves are by definition unique and unlike any other. So the more we develop and

discover our personal truths and passions, the more we experience the isolation of setting

ourselves apart from our former selves and from others. The ultimate sacrifice in

personal growth is giving up a sense of belonging, even if it is belonging and being

beholden to a set of sanctioned behaviors that is not true to one's own nature. Yet

ironically the search for authenticity is the most unifying feature of existence. It is the

quest that restores the ultimate sense of belonging to and in an abundant, miraculous, and

benevolently evolving universe.

We project selflessness and altruism onto religious figures such as Mother

Theresa and other ascetic and celibate spiritual leaders and onto heroes such as the

firefighters who lost their lives in the World Trade Center. We project victimization on

abducted children, injured animals, and those who suffer from diseases, such as breast

cancer and AIDS, that have inspired various causes célèbres, postage stamps, and fun

runs. In the mythology of karma, a soul chooses to be born into a life of hardship and

disability to teach humanity about sacrifice.

Horses have always willingly sacrificed for their

human companions. Mohammed was said to have corralled

100 horses and withheld water from them for three days in the

desert. When they were half-crazed with thirst, he let them

out. As a test of loyalty, he then ordered the horn of battle to

be sounded. All but five horses ignored the call. These five—

all mares—who denied themselves in order to answer the

battle cry became beloved of Mohammed. They were known

as The Five Mares of the Prophet and their foals were deemed

asil –pure of blood.

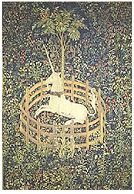

A striking allegory of Willing Sacrifice is the unicorn

myth old by the third century Christians in the parables of the

Physiologus and their later representations in the bestiary

fables of the Middle Ages. The unicorn myth handed down

through Rome and translated and embellished across Western

Europe portrays the unicorn as a fierce and solitary beast. By

dipping his horn in water poisoned by the venom of the snake,

a symbol of the Devil, the unicorn purifies it for all the animals to drink. The unicorn

cannot be captured except by a virgin, who lures the unicorn into her lap. When he has

thus been lulled to sleep, the hunters spring out of the woods and stab the unicorn to

death. In some versions of the tale, he is resurrected by the juice of pomegranates,

symbol of life and fertility, and is given to the king.

The parable is likely an attenuated form of earlier Pagan myths in which the

charms that attract the unicorn are anything but suggestive of virginity. Yet the later

version was interpreted in Christianity to signify the Virgin Mary's attraction of the Son

of God, who incarnates, dies, and is reborn.

In animal sacrifice, including that of horses as in the asvamedha, humans are not

only sacrificing their own food to the gods, but are projecting their inner Willing

Sacrifice onto the animal. What other way is there to attempt to rationalize the cruel use

The Unicorn in

Captivity. 15c

tapestry. NY

Metropolitan

Museum of Art