the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 1 of 20

DAY MARES AND NIGHT STALLIONS

—

ARCHETYPES IN THE MYTHOLOGY OF HORSES AND HORSE DREAMS

by Beverley Kane

PART I

–

MYTH

,

ARCHETYPE

,

AND SOMARCHETYPE

Myths are the dreams of the race.

Dreams are the myths of the individual.

Sigmund Freud, Dreams and Myths, p. 73

[…]Excellent dream work can be done whether or not one knows these

myths and folk stories. When the dreams call up archetypal images, the

unconscious dreamer already knows what the basic story is, whether or not

the interesting parallels to sacred narratives in other distant and obscure

cultures are immediately available to consciousness. The universal themes

can be discovered by "ordinary" explorations of the images for their personal

associations and basic symbolic implications. The archetypal amplifications

drawn from knowledge of the religious and folk traditions of other cultures

enrich the work; but they are not necessary, since the same essential

symbolic dramas and relationships can be revealed by the dream images

themselves, even without their specific archetypal associations.

Jeremy Taylor, The Living Labyrinth, p 107-8

THE LIVING MYTH

Speed. Strength. Grace. Power. Beauty. Every physical horse is a living myth unto its

beholder. We do not require a book of fairy tales or a Joseph Campbell to articulate the

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 2 of 20

deep personal awe we feel in the presence of Horse. To see, smell, touch, fear, and

mount a horse in the flesh is to feel the stirrings of archetypal energies arising from at

least 35,000 years of human awareness of Horse.

When we encounter Horse in waking life, she already possesses a dreamlike

quality. When we encounter Horse in dreams, we apprehend the living myth in

manifestations that are easily related to the magic she evokes in waking life. In She Flies

Without Wings: How Horses Touch a Woman's Soul, Mary Midkiff says, "A horse's

body and limbs are not just palpable but symbolic, not just functional but suggestive."

The nature of myth as something larger than life, a story on steroids, begs for

protagonists that, like Horse, are literally—and so figuratively—more momentous than

ourselves.

For contemporary cultures no longer dependent on the horse for food, draft, or

transportation, the living horse has ceased to be part of daily experience. If we see him at

all, it is in parades or mounted patrols, from a car window on a drive in the country, in

televised sports, or, uncommonly, as an aide in hippotherapy, therapeutic riding, equine-

assisted psychotherapy, and equine experiential learning.¹

The mundane associations having receded from our experience, what is preserved

and magnified are Horse's mythic qualities. Urban children become familiar with Horse

mainly through folk and fairy tales, movies and television. For them, only a mythical

relationship to horses exists. Yet even children who grew up on farms with horses retain

a sense of wonder and love for them. When Horse enters our dreams, her magical

qualities emerge whether or not we are currently in a relationship with a waking life

horse.

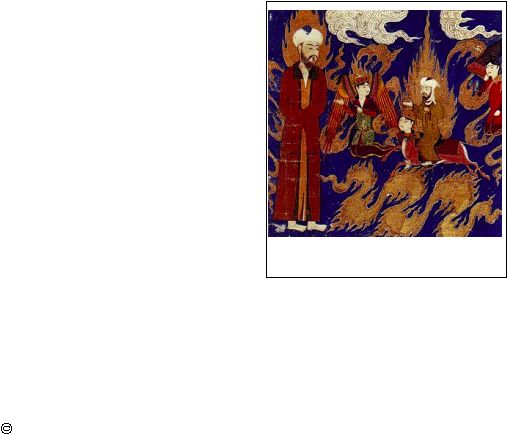

Most folk tales portray Horse as

extending the physical abilities of his rider and

so becoming an accessory to the Hero's quest.

He is literally and figuratively a means of

transport across the terrain of the tale's setting

and into the internal landscape of the Hero's

journey of self-discovery and awareness. In

Egyptian, Greek, Armenian, Norse, and Hindu

mythological traditions, horses pull the sun (and

sometimes the moon) across the sky. Al Borak,

a horse with the head of a woman and the wings

of an eagle, raises Mohammed to Seventh

Heaven. Bucephalus, a horse mythically

enhanced from historical record, carries

Alexander the Great into victorious battles.

Gods and goddesses such as Diana, Epona, and

Odin rode horses. So too, did Hades, god of the

Underworld, on his steeds Nonios, Abaster, and Abatos.

In the Rig-Veda of 3000 BC several references are made to the Aswin, the twin

sons of the sky Dyaus, and brothers of Usha the Dawn. The Aswin were gods with horse

heads and their sister Usha brought forth the dawn on her horse-drawn chariot. The Book

Mohammad ascending to

Seventh Heaven on Al Borak

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 3 of 20

of Revelations in the New Testament foretells the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

who will usher in the end of the world, the second coming of the Messiah, and God's

vanquishing of all evil. Muhammad, Vishnu, and Christ are all prophesied to return on a

white horse.

In many tales, Horse is an independent agent who corresponds to a singular

physical or psychological type. Pegasus alone stood among the Greek pantheon as a

god, sprung from the sea god Poseidon and the bleeding head of Medusa. Pegasus was

sacred to the Muses, and from his hoof sprang the Hippocrene fountain whose waters

conferred the gift for poetry in those who drank from it. No one was able to mount

Pegasus before Bellerophon sat astride him.

Bellerophon could not tame Pegasus until Athena

visited him in a dream. She handed him a golden

bridle and bade him ride Pegasus to defeat the

monstrous Chimaera. When Bellerophon awoke, he

held the golden bridle in his hands. Thus the bridling

of Pegasus symbolizes the rationality of Athena,

goddess of Wisdom, overcoming the instincts and

uncontrollable passions, represented by Pegasus in

his wild, unbridled state. The story also links the

dream world to the waking world. We are reminded

of our ability—the necessity—to use will and reason

to manifest in the physical the gifts from the seemingly chaotic, ephemeral, and

disconnected world of dreams, instincts, and imagination.

When we tell stories such as Good Luck Horse, Bad Luck Horse, recounted

below, we endow Horse with his own agency. When we examine horses in the dreams of

contemporary people, we will note whether they act as free agents or as physical

extensions of the dreamer.

ARCHETYPES AND PROJECTIONS OF MIND AND BODY

PSYCHOLOGICAL ARCHETYPES

Archetypes (Greek arche, original or beginning + type, form or pattern) is the Jungian

term for the blueprints for human personality and character essences that exist across all

cultures, throughout all time, in every individual. They are the straight-from-central-

casting roles that each society clothes in its own customs and prejudices—loving mother,

wise old man, beautiful princess, knight in shining armor, evil fiend, god and goddess,

beloved baby animal.

The entire cast of archetypes performs in every human psyche, usually in the

wings where we are unaware of them. Each of us is an omnipotential personality,

capable of expressing every archetype. Myths, folk legends, and fairy tales—remarkably

similar in all languages and cultures—are stories built around archetypal themes. Noting

|

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 4 of 20

these cross-cultural similarities, twentieth century psychiatrist and mystical intellectual

Carl Jung postulated a collective unconscious—the universal repository of all human

beliefs, knowledge, patterns, and experience that has not come to conscious awareness.

The collective unconscious is like a library of millions of books that taken together

reveal the infinite possibilities for the past, present, and future of the psyche. Taking

books out of the library is the act of making unconscious patterns and beliefs become

conscious.

Archetypal dramas come to us in folk tales and in night time sleeping dreams.

We also see them in waking dreams, those highly symbolic or highly charged events that

seem to happen to us—our triumphs, tragedies, lucky breaks, “accidents,” and illnesses.

In Jungian psychology, the work of a lifetime is the process of individuation in which

one attempts to integrate all the archetypes into consciousness of the Whole Self. In this

process, and in common with the mystical traditions of every world religion, we

recognize the fundamental unity of all beings and all experience.

To the extent that we have not acknowledged, embraced, and integrated all

possible archetypes within our own psyches, we will forever project them outward onto

others. Projection is the act, often unconscious, of attributing or blaming one’s feelings,

thoughts, circumstances, and attitudes to or on other individuals, racial or ethnic groups,

or animals. Everything we experience as otherness, external to ourselves, represents, in

part, a projection of our internal states upon our mates, parents, children, enemies,

heroes, and animal companions. When our unconscious projections lead to hateful

emotions, destructive behaviors, or dangerous infatuations, we damage our relationships

and ourselves. When we read myths and folk tales, we can harmlessly project our

unacknowledged archetypal roles onto the heroes, lovers, villains, and animals of fiction.

Children do this quite naturally and playfully by becoming monsters, witches, and fairy

princesses for Halloween.

In myth and folk tale, whether idolized or demonized, Horse appears in forms

that correspond to all the major Jungian archetypes we meet below—Anima and Animus

(Gender Complement), Dark Shadow and Bright Shadow, Trickster, Hero, and Willing

Sacrifice.

ARCHETYPES OF THE PHYSICAL BODY

Archetypes as Jung defined them are psychological concepts that press down like

cookie cutters on the dough of our personality and character. However mental constructs

are insufficient to represent all our projections onto Horse. We also project onto him our

nonverbal sensations of size, strength, balance, grace, coordination, agility, and speed.

The body has its own unconscious material that needs to be integrated into the Whole

Self. As is attested to in research on cellular memory and in some sudden changes in

personality in organ transplant recipients, the body has its own consciousness.² Like

concepts of intuitive empathy, mental telepathy, and emotional sympathy, we can

postulate a somatopathic function that is body-to-body. Just as tendon reflexes like the

knee-jerk reaction are mediated by the spinal cord and do not need the brain,

somatopathic projections are not relayed via the cognitive brain for their enactment. If

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 5 of 20

you have ever found yourself involuntarily and almost unconsciously bobbing your head

to a jazz beat, you've experienced a somatopathic response to the music.

Physical qualities are not adequately addressed in psychological archetypes.

Physical archetypes are separate but equally primal and universal. They exist in the

language of visceral repertory that the body understands on its own terms.

The body

does not merely react to ideas. It has its own primary apprehension and response. Martial

arts teach us that our mental states can be secondary to how we center, balance, and

move our bodies.

Let us suppose the existence of somarchetypes of the physical body's universal

primordial experiences.

*

The forms, shapes, and sensations experienced as Other, both

animal and human, receive projections from the sensory unconscious. In waking life and

in dreams, we project somarchetypes onto animal bodies and probably onto plants and

inanimate objects as well.

†

We project our imagined versions of tallness and shortness,

strength and weakness, skinniness and fatness, baldness and hairiness, vaginas and

penises, onto those who have attributes unlike our own but known to the collective

physical unconscious of which

we are part. We project our

undesirable, rejected Dark

Shadow somarchetypes onto

disabled or disfigured forms.³

We project our desirable, ideal

Bright Shadow somarchetypes

onto Olympic athletes, beautiful

ballerinas, and horses.

When we dream of

animals, one layer of the dream

is the dream body representing

itself as an earlier stage of our

physical development. The

memory of these forms is stored

over the millennia of evolution in

the consciousness of our cells.

A now largely discredited

theory of human embryonic

development states "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny."

‡

In the figure to the right,

executed, some say fraudulently, by late the late 19th century German biologist, Ernst

Haeckel, the human fetus in its nine months of development passes through forms that

resemble stages of evolution—from fish to amphibian to bird to "lower" mammal to

*

From Greek soma-, body. The term somatype might have been preferable, however it was already used

in the early 1940s by American psychologist William H. Sheldon to describe ectomorphs, mesomorphs, and

endomorphs.

†

Hence we have the Gestalt technique of being all characters and objects in our dreams.

‡

This concept means that the gestation, or coming into being (ontogeny), of each "higher" animal passes

through all the stages of evolution of each kind (phylum) of "lower" animal.

Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny. Ernst

Haeckel, 1868.

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 6 of 20

"higher" mammal.

In an analogous way, oneirogeny—the

creation of dreams by the dream ego—recapitulates

mythogeny. That is, dreams reënact the history of

myth and replay the primitive, modern, and universal

dramas of myth, legend, and fable. We dream

ourselves in more primitive physical as well as

psychological forms. Scenarios of animals behaving

idiosyncratically and other fantastic dream scenarios

lend the power of myth to our night dreams. That is

what Freud meant when he said, "Myths are the

dreams of the race; Dreams are the myths of the

individual."

EVOLUTION OF THE ARCHETYPE—FROM DARWIN TO DISNEY

Horses evolved 60 million years ago as Eohippus, a 4-toed, leaf-eating forest dweller

with approximately the habitus of a medium-size dog. Today's horse, Equus caballus,

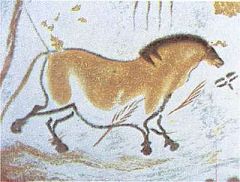

has been known for 20 million years. Late Paleolithic (-35,000 to –8000

*

) humans

hunted wild horses for food, evidently used them in ritual, and vividly depicted them in

cave art found all over Europe and, from a later period, in Asia Minor.

As an herbivore, the horse preys on no other animals, but is itself the target of

predators such as large cats and wolf packs. Most horses take flight under stress, but

when domesticated for ranching and battle, have been known for their bravery,

aggression, and selflessness. Some historians have proposed that the horse was first

domesticated by migratory reindeer herders in Northern Europe, who by –5,000 rode

reindeer and hunted horses, and somewhat later by the Proto-Indo-Europeans on the

Ukrainian steppes.

Beginning in the -3rd millennium, and over a period of 3,500 years, pastoralist

horse peoples from the Pontic-Caspian steppes began a methodical migration into

Europe, Anatolia (current day Turkey), the Indus region, and Western Siberia. The new

settlers underwent in part a syncretic absorption of the agrarian and mercantile native

societies. There is also archeological evidence of horse and chariot warfare, whereby

invaders forcefully conquered indigenous populations. In essence, the horse evolved

from a draft animal, to a warrior's steed—both harnessed to chariot and mounted—to a

form of general transport.

4

As the horse evolved in relation to humans, from food source in –35,000 to

domesticated laborer in –5000 to warrior steed in -2000 to sporting companion, he

appeared in different roles in myth and projection. We can only wonder what the

Lascaux cave artists were thinking in –14,000 when they painted horses inside the caves.

Were they thinking in terms of art for art's sake, religious iconography and ritual, or

*

Negative numbers designate dates "Before Christ" or "Before the Common Era."

Ivory carving of a horse

found at Hohle Fels Cave

in southern Germany. –

33,000

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 7 of 20

dinner?

5

By the first millennium, numerous

cultures abound with myths, folk tales, and

rituals involving the horse, including a form of

horse suttee—where horses were buried with

their masters.

Until recently, horse tales were told by

and to people who were familiar with physical

horses in daily life. In the age of the tractor and

the automobile and the snowboard, horse myths

are spread by the mass media to people,

especially children, who have little or no contact

with live horses. Old movies such as National

Velvet, the Black Stallion, Ben Hur, and Equus, and newer movies such as Spirit, Lord of

the Rings, Seabiscuit and Hidalgo proffer mainly archetypal images to a new generation

of dreamers.

The following sections describe the most significant Jungian archetypes and how

the horse portrays each archetype in mythology.

ANIMUS/ANIMA/GENDER COMPLEMENT

Animus and anima are the archetypal figures that hold, respectively, masculine and

feminine qualities. Masculine, or yang, qualities are traditionally active, penetrating,

aggressive, assertive, hard, dominant and rational. The feminine, or yin, is associated

with passivity, acceptance, nurturing, receptivity, envelopment, softness, and intuitive

processes.

In Jung's time, the animus was a woman's "inner man" and the anima was a man's

"inner woman." In a predominantly heterosexual society

*

conditioned by the persistent

influences of the 20th century, Jung's definitions remain relevant and useful in the

interpretation of dreams and myths. But because masculine and feminine do not

necessarily equate with or attach to biological males and females, and because there are

so many variations of intergender and transgender identities, the term gender

complement denotes the set of opposite or missing gender qualities that complete each

individual. Strong projections onto one's gender-complementary person are often

experienced as sexual attraction or falling in love.

One of the more remarkable aspects of a living horse is that he dually expresses

both strong masculine and strong feminine qualities. On one hand the horse's physical

powers suggest the strongman figure whom Jung's student Maria-Louise von Franz uses

to exemplify the wholly physical man, one of the four stages of the animus.

6.7

On the

other hand, in The Tao of Equus, Linda Kohanov claims that horses relate to the world

*

Demographers estimate that between 5 and 9 percent of the US population self-identify as gay, lesbian,

bisexual or transgender—Harris Interactive www.harrisinteractive.com/pop_up/glbt/ 2004

Cave drawing at Lascaux,

France. –14,000

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 8 of 20

from a primarily feminine, or yin, perspective:

As a result, the species is a living example of the success and effectiveness

of feminine values, including cooperation over competition, responsiveness

over strategy, emotion and intuition over logic, process over goal, and the

creative approach to life that these qualities engender.

Especially when gender-based philosophies such as feminism, as in Kohanov's

case, are the framework for one's observations and interpretations, it is tricky business to

map masculine and feminine onto men and women, much less onto mare, gelding, and

stallion. Labels aside, we observe that horses exhibit behaviors that, even within a single

horse, seem to be paired opposites: big and strong, yet shy and fearful—always a prey

animal, never a predator; stubborn and headstrong yet willing and large of heart; hardy

yet sensitive; easily domesticated and trained, yet (except when abused) forever wild,

free, and unpredictable; quick to take "offense," yet immediately forgiving.

In equine-assisted psychotherapy and equine experiential learning, patients and

participants are frequently, and usually unconsciously, drawn to horses that mirror some

aspect of the person's gender-complement relationships. These affinities, which can be

mutual from the horse's point of view, often enact the archetypal dramas of the human

relationships. For example, Kohanov presents the case of a smart-women-foolish-

choices type of client named Joy. In Joy's initial equine-assisted psychotherapy session,

she has "an overwhelming attraction to a horse who mirrored the traits of aggressive men

in her life, and [an] initial inability to recognize the danger this horse represented."

A striking enactment of the anima/animus dynamic with horses was the elaborate

and, to the modern mind, gruesome and grotesque ritual of the asvamedha and its Roman

derivative, the October Equus. Dating from thousands of years ago, and last performed

in the 18th century, the asvamedha is described in the Rg Veda as the merging with—in

some retellings, copulating with and then devouring—the sacrificial horse.

*

In this ritual, a stallion is set free for the period of one year. It roams far and

wide, accompanied by 400 of the king's warriors who assure his freedom to wander at

will and at the same time prohibit him from mating. At the end of the year, the stallion is

ritually killed and the king's favorite wife is placed under wraps with him. She lies with

the dead stallion for a full day and mates with him. The next day, the stallion is

dismembered into three parts –for each of three classes of society: warrior, priest, and

herder-cultivator—and roasted. Portions of the meat are sacrificed to the gods and

portions are eaten. Thus the king's wife not only ritually integrates her own animus

archetype of male potency, but the king himself courts power, fertility and abundance

vicariously through his living anima.

T.C. Lethbridge describes the complementary ritual, which he personally

witnessed in Ireland in the 17th century, wherein the king physically mates with a mare in

an enactment of union with the Divine Sovereign Goddess. In this Ulster ritual, the mare

is also divided into three parts, which are boiled to form a broth in which the king bathes

and which are then consumed.

*

The Proto-Indo-European root word ekwo-meydho, or horse-drunk, contains the root of our word "mead"

as an alcoholic beverage, and suggests that such horse rituals antedate even the antiquity of the Vedas.

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 9 of 20

Both the Vedas and the Celtic myths relate the deeper significance of physically

mating with and devouring the horse. The act is not just a fertility rite, but the union with

the Divine. In an essay on the Universe as a Sacrificial Horse, Swami Krishnananda

describes the elaborate rituals of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad in which the horse of the

asvamedha sacrifice is the object of consecration and meditation. In this Upanishad, the

horse "becomes a piece of contemplation which is the avowed purpose of the

Upanishad—to convert every act into a mode of contemplation, to transform every

object into the Universal Subject." In effect, the mating of anima and animus in our

personal relationships is a ceremony of ecstatic union with the divine,

Throughout the amateur equestrian world, there is a marked preponderance of

girls and women. During the lunch break at a local

horse show, one dad and I were noting this gender

imbalance as we watched his 12-year-old daughter

compete in her all-girl class. I asked him, "Why do

you think this sport appeals so much more to girls?"

He shrugged and replied, "They want something

powerful between their legs." Whether or not this

rather wan and nerdy Silicon Valley type was

experiencing strong projections of his own anima,

there is probably some truth to his assessment.

There is certainly some appeal for girls and women

of commanding and merging with a 1200-pound

beast who holds for us a certain animus archetypal

attraction and the somarchetypal attraction of

strength and power.

DARK SHADOW

Dark Shadow is the archetype that holds our rejected qualities such as "evil," violence,

ignorance, ugliness, weakness, decrepitude, and barbarism. When we fear we have these

qualities or have not recognized their positive alter egos, we project them onto our

enemies and villains, the "axis of evil," a despised relative or colleague, a race, nation, or

class of people.

8

Horses that are portrayed as behaving demonically, as if motivated by evil or ill

will, carry Shadow energy for the human race. In keeping with the gentle nature of

waking life horses, there are relatively few stories of mean, savage horses. In fact, most

horses in such tales derive their demonic qualities from shape changing gods, such as

Keshi or from their riders, who, like the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, are

themselves identified as the Devil or an evil witch.

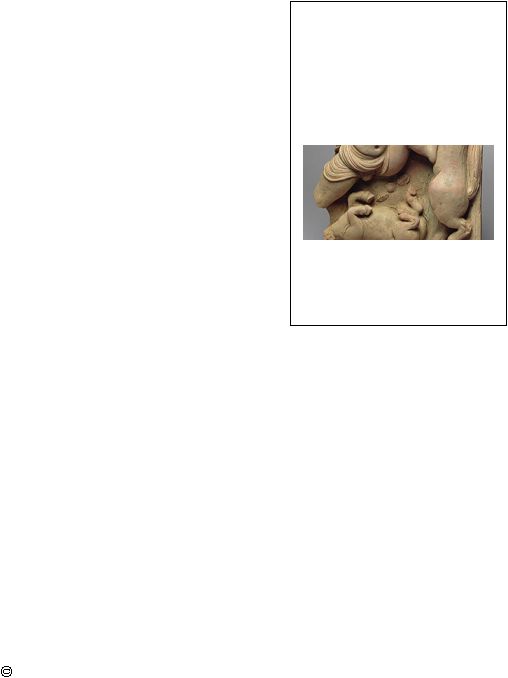

The illustration on the right depicts an episode from the early life of the god

Krishna, an incarnation of Vishnu, who periodically descends to earth to battle the forces

of evil. Here Keshi, a mighty demon in the form of a horse, has been sent to destroy

Krishna. The combatants glare at each other, eyes bulging: Krishna's from the intensity

Krishna battling the horse

demon Keshi. 5th century.

Uttar Pradesh, India

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 10 of 20

of resolve, Keshi's from the surprise of defeat, indicated by the corpse of his horse

below.

Centaurs, a hybrid race of horse and human, are

known for their barbarism. We must conclude that the

centaur's directives, coming from its head, are human.

While some centaurs, notably Chiron and Pholus, were

benevolent, most are depicted as having atrocious

appetites for debauchery, especially with liquor and sexual

intercourse. Centaur myths often feature them drunk and

attempting to abduct women.

In seasonal street parades in the British Isles, men

dressed as horses chase women as part of the pantomime.

The most famous of these festivals is the May Day antics

of the 'Obby 'Oss at Padstow in Cornwall. Men dressed as a full-skirted horse attempt to

capture women under the folds of cloth. To be caught in such a way is supposed to bring

a pregnancy to the married and a fine husband to the single miss. The frolic relates to the

horse as a fertility (and perhaps potency) symbol who, as in the asvamedha rites, also

ensures a rich harvest. Thus a woman's worst nightmare of a being molested by a

Shadow figure is transformed into an enactment of potency and fulfillment with an

Animus figure. In fact, all archetypes show protean forms that merge and shift and

become one another.

BRIGHT SHADOW/THE DIVINE/HERO

Bright Shadow is the archetype that holds our esteemed qualities such as goodness,

rightness, intelligence, creativity, beauty, entitlement, talent, and power. When we fear

we do not have these qualities, or are blocked by our inhibitions from acting on them, we

project them onto movie stars, elite athletes, heroes, gods, saints, and pets or totem

animals.

Most horse myths are tales that depict horses in heroic deeds of strength, speed,

and endurance. While many of these stories portray horses in battle, there is a delightful

legend from China, thousands of years old, where the horse acts as a different kind of

hero.

In this story, The Good Luck Bad Luck

Horse, a lonely little boy, the son of a man

wealthy with horses, longs for a horse of his

own. The stern Father will not give the boy a

horse, so he makes one out of paper. A wizard

hears the boy's wish for a real horse and

makes the paper horse come alive. But

because the boy forgot to draw eyes on his

horse, the little pony cannot see. It proceeds to

blindly stumble through the Father's garden,

trampling everything in its path. The Father banishes the horse, whereupon the wizard

Centaurs

|

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 11 of 20

takes pity on him and gives him the power both to see and to fly.

The horse flies off, finds a wife, and after many years returns to the little boy,

who is now a grown man in a kingdom on the verge of war. The horse and his mare fly

off to the battleground and speak to the horses of the enemy soldiers. All the horses

collude to bring the warring armies together in the river, where they cannot shoot

eachother but get tossed into the water and can only laugh at themselves.

After peace breaks out, the horse and mare return to the kingdom of the boy-

become-man and his Father. The little horse has proven his worth and everyone lives

happily ever after. So the horses, onto which the small boy projects his hopes and

dreams, come home to roost.

The somarchetype of the horse captures our strongest Bright Shadow projections.

When I watch horses galloping across a field or bursting forth at turn out, I long for a

tiny part of that energy and strength. My body attaches itself to the powerful movement.

Whether we envy their physical prowess or idolize and idealize them as noble savages,

we are prone to investing horses with that which we yearn for and cannot fully attain.

Many myths and dream images portray Horse as the vehicle for mythical journeys and

magical powers.

TRICKSTER

The Trickster archetype holds the imp sitting on our shoulder who says, "Lighten up.

Think different. Let go." He opposes the subpersonalities who are stubborn, serious,

morbid, doctrinaire, addicted to stability and terrified of change. He attacks our fixed

ideas and our attachment to the way things are. Trickster seeks to undermine our pride,

especially when it is vested in a static self-image that stunts our spiritual growth.

Because duplicity and chicanery are generally considered unethical in Western

society, the Trickster archetype of the used car dealer or the fox is often met with the

same antipathy as is felt toward the Shadow. But Trickster is the fellow who can get us

to laugh at ourselves. He is the voice of a black person using the "n" word to his brother;

he is why we pay extra to sit in the front row at comedy clubs and get harassed by the

headliner; he is why kings had court jesters. The fool in Shakespeare is particularly

aware of when his king crosses a moral line and is in the play to remind the king of his

own folly with thinly veiled derision.

Unlike Shadow with whom we can more or less choose our skirmishes, Trickster

comes to us unannounced and on his own terms. He is the great cosmic banana peel of

the unconscious. We let him in by giving him something to work with—our hubris, our

conscious and unconscious assumptions, our prejudices, our fears, our puffed up images

of ourselves. He creates a stampede among our sacred cows when they have outlived

their usefulness or tied up our energies in old structures and systems that need to be

overturned and overhauled. Trickster forces us to break out of our stereotypes and our

boxes, whether they've been imposed by our families, our culture, or ourselves.

Carl Jung states that the trickster archetype is "a primitive cosmic being of

divine-animal nature, on the one hand superior to man because of his superhuman

|

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 12 of 20

qualities, and on the other hand inferior to him because of his unreason and

unconsciousness." This description helps explain why in mythology, Trickster often

appears as animals—Coyote, Blue Jay, Raven, Spider, Snake, Monkey, and Horse.

The horse as Trickster abounds in Celtic folk tales, where horses take the form of

shape-shifting water horses such as the Irish Each Uisge (ach (horse), ish-kee (water)) or

the Scottish Kelpies. Typically the water horse wears a golden bridle that appeals to

human greed. Although travelers are warned not to trust horses that appear at rivers and

lakes, the weary human wants so badly to believe in the human that promises easy

passage across the water. Immediately the human is on its back, the Kelpie dives to the

bottom of the body of water where the human suffocates and drowns. The story seems to

be a cautionary tale about get-rich-quick schemes and attempts to take short cuts on the

emotional and spiritual journey represented by the water.

One manifestation of Kelpie was a handsome man, no doubt seducing women

with the promise of the false animus. In variations on this story, if the human tells the

truth, s/he is released to the surface.

Sometimes the horse trickster rewards the trust placed in him. In a most

enchanting Celtic tale, The Bedraggled Horse, a huge homely draft horse takes 17 of the

warrior Cuchulainn's men down to a fairyland under the sea in an almost shamanic

journey. Once there, the horse is transformed into a brilliant, beautiful steed and the

underwater inhabitants pledge always to come to the aid of the humans.

The allegory of the water horse is one of diving deep into the unconscious,

especially into unconscious emotions. If one bravely acknowledges the feelings that

reveal her personal truths and values, at the expense of her tightly-held conditioned

misjudgments, she receives the gift of Trickster.

Living horses often play the role of trickster—ducking us in the water, getting

away with little bucks on a fresh spring day, stealing carrots from our back pockets, and

generally reminding us to keep a sense of humor about ourselves.

WILLING SACRIFICE

Willing Sacrifice is the archetype that holds the nature of our transpersonal, transcendent

Self, the part of our unconscious that is able to see beyond the temporal and material. It

is able to withstand pain and suffering for the greater good of our Whole Selves and for

the sake of others. It is the sorrowful renunciation of the earthly for the sake of the

Divine. It is the soul's consent to experience suffering in order to elucidate the nature, the

phenomenology of suffering. Suffering provides the counterpoint to joy so that joy may

be felt all the more strongly by being juxtaposed to its opposite. The most prevalent

allegory of Willing Sacrifice in the last two millennia is that of Christ dying on the cross

for the sins and salvation of humanity.

The word sacrifice comes from the Latin sacrificium, which is a combination of

sacer, meaning something set apart from the secular or profane for the use of

supernatural powers, and facere, “to make.” At one time sacrifice referred to a religious

act in which objects were set apart or consecrated and offered to a god. Our authentic

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 13 of 20

selves are by definition unique and unlike any other. So the more we develop and

discover our personal truths and passions, the more we experience the isolation of setting

ourselves apart from our former selves and from others. The ultimate sacrifice in

personal growth is giving up a sense of belonging, even if it is belonging and being

beholden to a set of sanctioned behaviors that is not true to one's own nature. Yet

ironically the search for authenticity is the most unifying feature of existence. It is the

quest that restores the ultimate sense of belonging to and in an abundant, miraculous, and

benevolently evolving universe.

We project selflessness and altruism onto religious figures such as Mother

Theresa and other ascetic and celibate spiritual leaders and onto heroes such as the

firefighters who lost their lives in the World Trade Center. We project victimization on

abducted children, injured animals, and those who suffer from diseases, such as breast

cancer and AIDS, that have inspired various causes célèbres, postage stamps, and fun

runs. In the mythology of karma, a soul chooses to be born into a life of hardship and

disability to teach humanity about sacrifice.

Horses have always willingly sacrificed for their

human companions. Mohammed was said to have corralled

100 horses and withheld water from them for three days in the

desert. When they were half-crazed with thirst, he let them

out. As a test of loyalty, he then ordered the horn of battle to

be sounded. All but five horses ignored the call. These five—

all mares—who denied themselves in order to answer the

battle cry became beloved of Mohammed. They were known

as The Five Mares of the Prophet and their foals were deemed

asil –pure of blood.

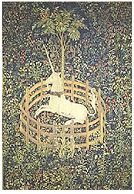

A striking allegory of Willing Sacrifice is the unicorn

myth old by the third century Christians in the parables of the

Physiologus and their later representations in the bestiary

fables of the Middle Ages. The unicorn myth handed down

through Rome and translated and embellished across Western

Europe portrays the unicorn as a fierce and solitary beast. By

dipping his horn in water poisoned by the venom of the snake,

a symbol of the Devil, the unicorn purifies it for all the animals to drink. The unicorn

cannot be captured except by a virgin, who lures the unicorn into her lap. When he has

thus been lulled to sleep, the hunters spring out of the woods and stab the unicorn to

death. In some versions of the tale, he is resurrected by the juice of pomegranates,

symbol of life and fertility, and is given to the king.

The parable is likely an attenuated form of earlier Pagan myths in which the

charms that attract the unicorn are anything but suggestive of virginity. Yet the later

version was interpreted in Christianity to signify the Virgin Mary's attraction of the Son

of God, who incarnates, dies, and is reborn.

In animal sacrifice, including that of horses as in the asvamedha, humans are not

only sacrificing their own food to the gods, but are projecting their inner Willing

Sacrifice onto the animal. What other way is there to attempt to rationalize the cruel use

The Unicorn in

Captivity. 15c

tapestry. NY

Metropolitan

Museum of Art

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 14 of 20

of mares and the sad plight of PMU (pregnant mare urine) foals to produce estrogen for

human females?

Many of the living horses with whom we come into relationship have in a sense

sacrificed their freedom and bent their wills in order to bond with us as partners in work,

play, and discovery. We too enact the drama of willing sacrifice, giving up both luxuries

and even necessities to provide food, shelter, amusement, and companionship to our

horses and mucking out their stalls at 5 AM on a dark, freezing winter morning.

WARRIOR

A special subset of the Hero archetype deserves separate mention here because it is so

indelibly associated with Horse and set on horseback. From Genghis Khan to the Iliad to

cowboys and Indians, from The Lord of the Rings to El Cid to Ben Hur, the warrior

archetype holds for us notions of bravery, courage, justifiable

aggression, and glory. The bloody images of battle both

antagonize us with their violence and gore, and arouse us with

their massive displays of power and ruthlessness. Richard

Strozzi-Heckler, in his book In Search of the Warrior Spirit

describes his time spent training United States Special Forces

(Green Berets) and other top flight military troops in the art of

aikido.

*

He describes the nature of the true warrior when war

was a gallant hand-to-hand, horse-to-horse combat, not one

fought impersonally with missiles and guns and bombs and

other actions at a distance.

It is ironic that the wars fought today enact the failure

of the integration of the true Warrior spirit both by those who

fight and those who condemn the fighters. That is, hawks and

doves are eachother's Shadow archetypes. Pacifists do not

understand the basic human need to enact and integrate the Warrior. Warmongers

running unchecked use their armies for their own Shadow plays. They do so with hatred

and mass destruction that is inimical to the Warrior spirit.

Outward Bound and ropes courses, corporate paint ball fights, and contact sports

attempt to express healthy forms of courage and aggression, but there is nothing like a

good old fashioned war, where one's very life is at stake, to bring home the lesson of the

Hero and the Warrior, and their related archetype, Willing Sacrifice.

†

It is ironic that one

of the most prominent wars being fought today, that in Iraq, was formerly the

battleground of the most courageous and valiant war horses, fighting perceived infidels

then as now.

*

Strozzi-Heckler and his wife Ariana own horse ranches where Ariana teaches equine experiential

learning. The programs emphasize principles of somatics, martial arts, and the warrior spirit.

†

A popular computer software product is named Code Warrior—evoking the notion that nerdy little guys

who write code (computer programs) are capturing the warrior spirit.

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 15 of 20

HORSES IN THE TAROT—MYSTICAL CHIVALRY

The Tarot is a deck of 78 cards that, differentiating their upright from

reversed positions, depict 156 conditions of the psyche. The history of

the Tarot is obscured by ghost stories until the appearance of Italian

decks in the Middle Ages. In the absence of any objectifiable history,

the numerous decks must be taken at face value suggesting a

syncretism of multiple mythologies. Prior to the many PhotoShopped

desktop decks with pop and high tech imagery, the images and

traditions of the classical decks have been eclectically pagan,

Christian, Arthurian, alchemical, and Kabalistic.

In the Waite-Coleman Tarot, one of the most commonly used for divination,

there are seven cards depicting horses: The Sun, Death, the 4 Knights, and the 6 of

Wands. In all the illustrations, the horses are mounted, in portrayals of physical and

metaphysical transport.

In The Sun and Death, horses carry respectively the youngest

person and the oldest person in the Tarot—the crowned and

conquering child of the new aeon and the grim reaper himself. As in

many horse myths, the horse in the Death card is a psychopomp, one

who carries dead souls to their final resting place. The horses

contribute to the Tarot's framework of transition, cycles, and process.

In essence, the Tarot is like the Book of Changes, the I Ching, where

the only constant is change. The Death card in the Tarot, as death in

dreams, is one of the most reliable indicators and harbingers of

profound psychospiritual transformation.

Each of the four court cards represents the querent's evolving use of the energies

represented by the suits— wands (intuition), cups (emotions), swords (intellect), and

pentacles (sensation). Knights in the Tarot signify energies that the querent is in process

of integrating but has not fully mastered. The Knight's use of energy is,

in the chivalric sense, for the sake of the Other—the fragmented self

split off from the integrating ego who has not yet learned the mature

and confident use of that energy. In the mythos of chivalry, with its

values of courage, courtesy, honesty, courtly love, and service, the

Knight seeks his fortune in uncharted regions of consciousness. For

Waite, a 19th century mystic who was steeped in the esoteric

significance of the Holy Grail and who wrote books on the Arthurian

legends, Knights and their horses represent the Hero's journey to

spiritual wholeness.

SUMMARY

Horses are ubiquitous in the fables and legends of many different cultures. Like other

mythical figures, horses dramatize the Jungian psychological archetypes—roles or

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 16 of 20

caricatures derived from the experiences of a culture and present in the unconscious of

each individual within the society. Archetypes constellate the psychological

characteristics and identities that we unconsciously project onto other people, mythical

figures, and animals.

Horses also invite projections from the physical body—the somarchetypes that

constellate projected sensations of balance, speed, and strength.

When horses appear in dreams, one layer of the dream is the archetypal and

somarchetypal role of Horse. When we encounter horses in the flesh, our minds and

bodies consciously and unconsciously resonate with the stirrings of both psychological

and physiological archetypal energies.

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 17 of 20

ENDNOTES

1. Hippotherapy is the treatment by horseback riding of severely disabled persons by a

physical therapist, speech therapist, or occupational therapist. Therapeutic riding is the

schooling of high-functioning disabled persons by specially trained and certified riding

instructors. Equine-assisted psychotherapy is the treatment of psychopathological

disorders by licensed clinical psychotherapists, credentialed counselors, and life coaches.

Equine experiential learning, also known as equine-facilitated growth or equine-guided

education, is conducted by a variety of practitioners and guides for the purpose of

psychospiritual growth and transformation. All four kinds of horse therapies require

partnership with the horse and a horse handler, or equine expert, as partners.

2. In the passage quoted below, Jung describes the role of the physiological in

engendering symbolic systems: (my emphasis)

The symbols of the self arise in the depths of the body and they

express its materiality every bit as much as the structure of the

perceiving consciousness. The symbol is thus a living body, corpus et

anima. The uniqueness of the psyche can never enter wholly into reality, it

can only be realized approximately, though it still remains the absolute basis

of all consciousness. The deeper layers of the psyche lose their individual

uniqueness as they retreat farther and farther into darkness. Lower down,

that is to say as they approach the autonomous functional systems, they

become increasingly collective until they are universalized and extinguished

in the body’s materiality, i.e., in chemical substances. The body’s carbon is

simply carbon. Hence at bottom the psyche is simply world. In the symbol

the world itself is speaking. The more archaic and deeper, that is the

more physiological, the symbol is, the more collective and universal,

the more material it is. The more abstract, differentiated, and specific it

is, and the more its nature approximates to conscious uniqueness and

individuality, the more it sloughs off its universal character. Having finally

attained full consciousness, it runs the risk of becoming a mere allegory

which nowhere oversteps the bounds of conscious comprehension, and it's

then exposed to all sorts of attempts at rationalistic and therefore

inadequate explanation.

Jung, C.G. (1966) p. 173

In this passage Jung admits to a curiously Cartesian division of body and soul. One can

agree in that in zoological terms, the more physiological a symbol is, the more universal.

However, the physiological seems to holographically retain the characteristics of the

whole self. We speak of cellular memory, unique fingerprints, and experiences that are

held by the body and released in body work.

3. Michael Shea has assigned the Shadow archetype to the Body. He implies that the

psyche projects its Shadow onto the body.

The body is part of my shadow because it contains a long suffering history of

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 18 of 20

how the spontaneous excitement of life is killed, denied and rejected in

numerous ways until finally, the body becomes robotic and senseless. …

Touch therapists, body-centered psychotherapists and others who can read

the body will hear the recording of the rejected part of the self located in the

living tissue of the human body. It is the side too often denied or projected

onto others. …

As the 21st Century begins, the body, as shadow, becomes more

compelling. … The body becomes the repository of a lost mythology. This

mythology connects the living matter of my body to the earth and the spirit

world.

This concept is different from saying that the body itself projects unconscious material

outward onto, for example, horses.

4. There are several theories, none universally accepted, of how the Indo-Europeans and

their horses entered the historical record. There are mythic and counter-mythic academic

wars fought among cultural chauvinists (Indologists, Aryan supremacists, Marxists, etc),

feminist revisionists ("matrist historians" such as Marija Gimbutas) and their critics,

anthropologists, and linguists. The most cogent and agenda-inapparent meta-analyses of

the archeological and paleo-linguistic evidence as compiled by Mallory, Hayden, and

others suggest that the Indo-Europeans spread in several waves, by some combination of

invasion, slow migration with their own women and children, and diffusion with

acculturation, not necessarily in that order. Certainly if I had been a late Neolithic

farmer's daughter slopping pigs in the Pelasgians, I might have been quite attracted to the

dashing horsemen coming to trade in Corded Ware.

5. Modern man appears almost completely to have lost the ability to transmit

mental pictures, probably because this was the first skill he ceased to use

when he gained the ability to speak. If you could describe with your voice

what you were seeing, you did not need to transfer a mental picture. But

some primitive tribes still retain the skill and we have seen that Laurens

van der Post in his travels among the South African bushmen observed a

witch doctor gaze at the cave drawing of an antelope, throw himself into a

trance, and then so accurately describe the location where the antelope

was grazing that the hunters could go out and kill it.

Henry Blake, Talking With Horses

6. Von Franz, presumably following Jung's convention, refers to the four stages of the

anima and animus, as if there is a developmental sequence for each facet of the

archetype. In this hierarchy, the physical is trumped by the romantically esthetic

(emotional), which in turn is superceded by spiritual love (intuitive), which ultimately

gives way to wisdom. Examples from von Franz are, respectively, Gauguin's bare-

breasted Tahitians, Helen of Troy, the Virgin Mary, and the goddess Athena.

Other Jungians describe the chief manifestations of anima and animus as four

egalitarian functions—thinking, sensation, intuition, and emotion. The best description

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 19 of 20

of the facets are as Harding describes: Hetaera (beauty), Great Mother (compassion,

nurturing), Amazon (strength), and Wise Woman (seer) and Great Father (wisdom),

Hero (courage), Puer (frivolity).

7. There is an interesting difference here between the horse's physical capacity as a

somarchtype and as an archetype. When I feel the horse's body as an extension of my

own and as a compensation for my own waning strength as I age, I am projecting onto

the somarchtype of strength. When I look to a horse, typically a stalwart, older gelding,

to take care of me on the trail, I am projecting onto the archetype of Wise Father or

physical protector.

8. The Shadow is typically a person of one's same gender for whom one feels an

irrational hatred. A striking example of projected Shadow qualities is the murderous gay

bashing committed by homophobic heterosexual men. These men experience

uncontrolled rage when they see or imagine effeminate behavior in another man.

Because the perpetrators of these hate crimes have not embraced their own feminine

side—the softer, more nurturing, quiche-eating side that can cry in a tender moment—

they project Weak Woman as Shadow onto less macho males. Like the caricatured

effeminate-femininity pair, all negative Shadow qualities—even so-called evil—are

paired with a positive aspect of itself that needs to be integrated into the psyche.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blake, Henry L. Talking With Horses.

Edwards, Elwyn Hartley. The New Encyclopedia of the Horse. Dorling Kindersley.

London. 1994

Encyclopedia of World Mythology. Foreword by Rex Warner. BPC Publishing.

1970

Farrar, Janet and Russell, Virginia. The Magical History of the Horse. Robert

Hale. London. 1992.

Halpern, Mark. A Winter's Tale.

Hausman, Gerald and Hausman, Loretta. The Mythology of Horses. Three Rivers

Press. New York. 2003.

Harding, M. Ester. The Way of All Women: A Psychological Interpretation.

Longman's Green, 1933

Hillman, James and McLean, Margot. Dream Animals. Chronicle Books. 1997.

|

the archetypal mythology of horses

Copyright

2004-2021

Beverley Kane, MD

Page 20 of 20

Jung, Carl Gustav. Psychological Types. Collected Works Vol 6. Bollingen 1921

— and M.-L. von Franz, Joseph Henderson, Jolande Jacobi, Aniela

Jaffé. Man and His Symbols. Doubleday. 1964

—

The psychology of the child archetype. In Read H., et al (eds):

Collected Works Vol. 9. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

1966

Kohanov, Linda. The Tao of Equus—A Woman’s Journey of Healing &

Transformation through the Way of the Horse. New World Library.

2001

-

Riding Between the Worlds. New World Library. 2003

Krishnananda (Swami).

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad

krishnananda.org/brdup/brhad_I-01.html and hardcover book. The

Divine Life Society Sivandanda Ashram. Rishikesh, India.

Mallory, John P. In Search of the Indo-Europeans

McCormick, Adele von Rust and McCormick, Marlena Deborah. Horse Sense and

the Human Heart: What Horses Can Teach Us About Trust,

Bonding, Creativity, and Spirituality. Health Communications.

1997

Midkiff, Mary D. She Flies Without Wings-How Horses Touch a Woman’s Soul.

Delacorte Press. 2001

Shea, Michael J. The Body as Shadow. http://www.sheacranial.com/publications/

papers/paper_bas.htm 2000

Sheppard, Odell. The Lore of the Unicorn. Harper & Row. New York. 1979

Strozzi-Heckler, Richard. In Search of the Warrior Archetype.

Sylvia, Claire. A Change of Heart. Warner Books. 1998

Taylor, Jeremy. Dreamwork. Paulist Press. New York. 1983

-

The Living Labyrinth. Paulist Press. New York. 1998

Witter, Rebekah. Living With Horsepower! Personally Empowering Life Lessons

Learned. Trafalgar Square. 1998

- Winning With Horsepower! Achieving Personal Success Through

Horses. Trafalgar Square. 1999

|